Created: 14 October 2008 Update: 19 March

2014

& Below, Fortunatus Wright

some parts are copyright - https://gavin-chappell.co.uk

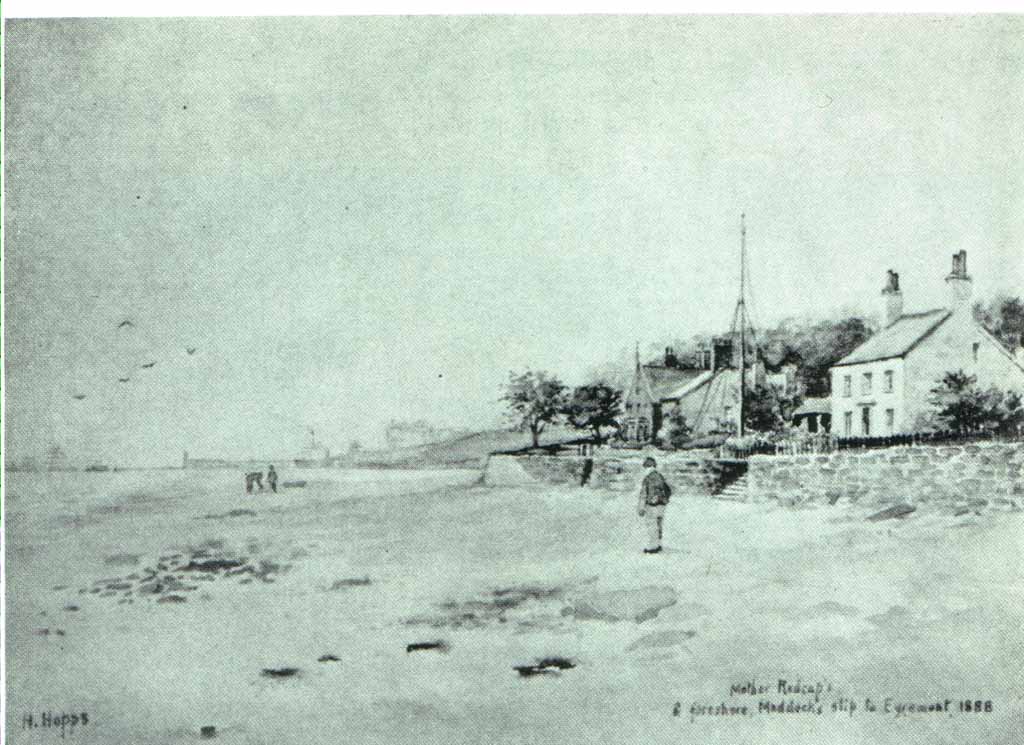

Mother Redcap's circa 1888 |

Old Mother Redcaps is an 18th Century nickname for an establishment, situated near Egremont, that the customs had rather wished was not there. A den of smugglers, and for sailors avoiding Press Gangs, Mother Redcap had a place in my heart from my teenage years, as I wandered along the foreshore, looking up at the building, still there in the 1960s, that was so mysterious and so compelling. In later years, namely 1999, the site was to become even more poignant when, in the Nursing Home that replaced it on the land, my mother died on May 18th. Growing up in the Swinging 60s on Merseyside, no building held such fascination as this. A Tudor building which looked the part. The tower on its roof, stories of hidden tunnels!! Mother Redcaps was built in 1595 by the Mainwaring family as a home, on a piece of moor land, just above high water mark of the River Mersey. The Mainwaring family were one of the main families in the Wirral. In the 60s when I last saw her, she resided on the embankment between Caithness Drive and Lincoln Drive, facing Liverpool's Dockland. Its names included The Halfway House, The White House and Seabank Nook, as well as mother Redcap's. Built of Redstone, the lower walls were nearly 3 feet thick and it had two mullioned lower front windows. The outer walls were covered with thick planking from wrecked ships. In due course of time this fell off and was not replaced. The front door was of made of oak, being five inches thick and studded with thick, square headed nails. A Mr Kitchingman found the remains of this door in a cellar when doing renovations in 1888. Markings on the door showed indication of there having been several sliding bolts. On the windows were found slots which gave evidence of strong shutters having once been fitted. There is, or was, evidence of a trapdoor fitted directly behind the oak front door. This led to a cellar concealed behind the door. In the event of the front door being forced, intruders would burst in and drop to the cellar which was 8 - 9 feet below them. Another passage from the back of the staircase in the passage from the south room to north room also led into the cellar. All this was still in existence in 1888. When the front door opened, the entrance to the south room was sealed, quite elaborate! |

|

Behind the stairs was a door leading to the kitchen at the back of the house and, from there, into a back yard. A small stream of good water ran through the rear of the premises. This supplied the house with water and was also used by small vessels moored nearby for their supplies. Also to the rear of the property was a Brew House. In 1840 it was noted for its strong dark ale. Another large cave or cellar was to be found underneath the south room. In 1930, someone noted that it "sounded hollow" beneath a greenhouse. Indeed, part of the yard was actually the roof of this cavern or cellar, being large sandstone slabs, supported upon large beams. On top of this stood a manure pile and a stock of coal, to complete the "disguise". To facilitate the arrival of "goods", part of the manure pile was removed, and slabs lifted to enable goods to be secreted below. In an old book about smuggling in the Wirral, there is mention of a tunnel leading from here to the "red Noses", a sandstone bluff at what is now New Brighton. This led to a hidden entrance in a large ditch which ran downhill from the direction of Liscard. A large willow provided an excellent, concealed, look out, whilst activities were conducted to the rear. This tree was cut down in 1889. Mr Kitchingman, in 1890, planted a cutting of the tree to the rear, which grew higher than the house itself. In the south room was found a hidden cavity of sufficient size to hide a man. also, in the same room, were hidden niches where sailors would hide wages and valuables, as well prize money from captured vessels. The present seawall was built by Mersey Docks & Harbour board in 1865. Outside the house stood a wooden seat. On one end of the seat was a wooden weather vane on a short wooden flagstaff. It was supposed to work with the wind but was in fact a signalling device. When the vane pointed towards the house it was safe to approach. When it pointed away, it meant stay away, danger. This was used mainly by smugglers. At the opposite end of the seat was a post with a sign upon it. A portrait of Mother Redcap holding a frying pan over an open fire with the words: "All ye that are weary come in

and take rest, |

In this image the tower of mother Redcap is quite prominent, on the left hand

side. |

|

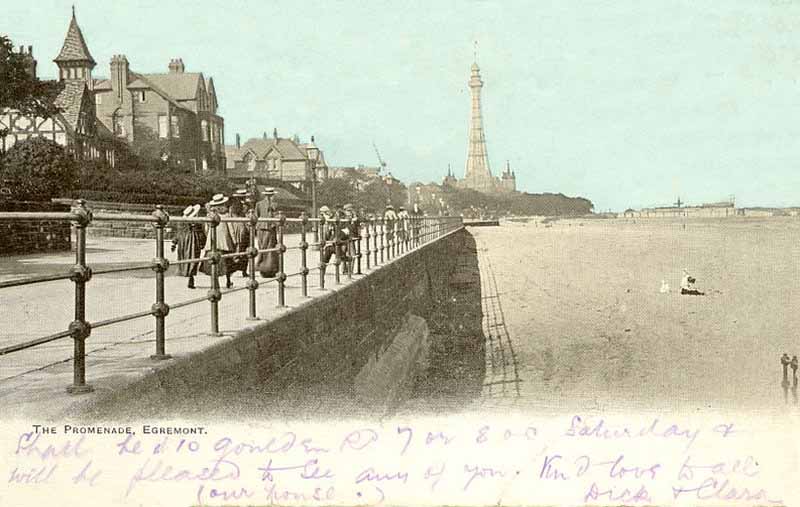

On January 6th 1839, a terrific hurricane lashed the region. Survivors of the Pennsylvania, Lockwood and Brighton were landed on the shore under shelter from the west, the wind being west to north north west; by the Magazine Lifeboat; assisted by the tug Victoria, and were brought to Mother Redcap's. A piece of lead weighing three and a half hundredweight was blown from the roof, being deposited on the foreshore at the low water mark. An account of the USS Pennsylvania can be read here In 1888, Mr Kitchingman, who was born in Withens Lane, later the Horse & Saddle Inn, retired from Legal work in Warrington and bought Mother Redcap's, which had previously been a fisherman's cottage. He gave the land in front of the house on the express desire that no carriages would be allowed to perambulate along it. The Mersey Dock & Harbour Board were planning to build the embankment right along this stretch, from Seacombe. When Royalty came to open an extension to the Navy League premises, carriages did use the promenade. This so enraged Mr Kitchingman that he left the house for use as a Convalescent Home for the people of Warrington instead of to the district. Being unsuited for this purpose, powers were obtained to set aside the wishes in his will, a Mr Robert Myers bought the house, opening it as a cafe. Bearing the name Mother Redcap's, again. I think it was maybe the late 1960s when I last saw Mother Redcap's. I was walking along a very dirty, sandy foreshore and I can recall looking up at its dilapidated state, wondering what stories it could tell. Effluence on the sands meant you also had to watch were you walked! Opposite and slightly up river, the Royal Liver Buildings stood in all its black, soot covered, glory as was the Cunard Building and the Mersey Dock & Harbour board (MDHB). A lot has changed since then. The river, running past Mother Redcap's, is quiet. No ships lie an anchor there anymore. Few ship venture beyond this point now. Most are container ships which use the docks at Seaforth, on the mouth of the river. The famous docks have all but vanished, a single ferry boat works her way between Seacombe, Woodside and Liverpool. I doubt if the Mersey has ever been as quiet as this in her history, a pale ghost of a busy past. I think it is significant that events such as the "Tall Ships Race" is an attraction that draws possibly hundreds of thousands to the region. These ships, which once filled the river with their forests of sails and masts in the days of Mother Redcap's are now the same spectacle that draws in crowds. When I returned to the river, in 2008, to watch these ships leaving the river, I watched from across the bay, from Crosby. The local Councils made a veritable fortune from parking fees on what was normally free parking areas and no parking cones were as numerous as the visitors along both sides of the river, particularly in the region of Mother Redcap's and patrolled by fluorescent coated officials with a greedy look in their eyes. On Seabank Road, above Mother Redcap's, I pulled over to speak on my mobile phone, and I swear these "vultures" must have been perched on nearby rooftops; they suddenly appeared from nowhere! The plus side to all this change is that the river is now classed as clean. Probably cleaner than it has been for over 500 years. The once dirty foreshore is relatively clean, large formations of dumped rocks have steadied the erosive elements of the tide. Excrement no longer litters the sands, by which children once played with their buckets and spades; but other, even worse, dangers now exist, unknown in my time, insane druggies needles!!

1857

On the shore in front of the house was a wooden seat made from timbers taken from wrecked ships. On one end of this was a short flagpole topped by what appeared to be a wind vane. In reality it was used by the smugglers to signal danger when the vane pointed away from the house. On the other end of the seat another post held a picture of Mother Redcap holding a frying pan over a fire, and underneath were the words opposite: |

In 1690, William III had his troops camped on The Leasowes awaiting ships to take them to Ireland. It is said that at that time despatches were conveyed to Chester from Meols and then to Mother Redcap's and then by fishing boat to Stoke and Poole instead of from Meols to Parkgate. (Stoke was apparently Seacombe, or very nearby Seacombe). Poole could have been another small region further up river. (Parkgate was not the landlocked town we know today, having been a thriving port and well known, and used, in Nelson's days). Earlier mention of the Privateer, Redcap, was made. She was used to take despatches from King James' supporters up to Stoke and Poole on the secluded reaches of the Mersey where many Ronan Catholic families dwelt. It is noted that "on one occasion 3 persons of some distinction were hurriedly landed at Mother Redcap's from a ship, horses ready, they galloped off towards "The Hooks". Very soon afterwards an armed boat crew landed from up river and made a hurried search". The Hooks were later identified by me as being in the region of what is now Duke Street bridge on the docks. The explanation being that certain refugees had made good their escape from Ireland and had intended to proceed up river to Stoke or Poole. An armed boat was lying in wait up river from Seacombe, discovered the ship discharging her passengers and had raced to intercept. Around 1750 a strange dispute took place at Mother Redcap's. A dead body had been found on the foreshore and taken to the house and in via the rear door and, later, passing out through the front door. "Certain people" claimed that if 12 bodies passed through a premises during a year, it gave right of way for the living to pass though at any hour, day or night. An attempt was made, once only, to gain access and a fierce fight ensued. After much discussion and advice, legal etc, the claim was refuted. It was almost certainly HM Customs and Coastguard trying it on! Another tale has mother Redcap described as a "comely, fresh coloured, Cheshire spoken woman" and that at one time she had a niece to assist her. Her niece was "very active but offhand in her manner, who married a Customs Officer". The first ever steam voyage from Liverpool to the USA left Liverpool in 1838. The Royal William, 617 tons, left the Mersey on 5th July. A party of the Liverpool Dock Trustees and ship owners assembled at Mother Redcap's to witness the departure. A cannon was fired from here as the ship passed. Overheard at this meeting was the belief that the ship would not get beyond Cork. It is recorded that Mr Kitchingman's father, when aged 20, saw both the seat and the signs when he stayed there awhile in 1820. Many years ago I remember seeing an image of this sign, but I can't recall where this was, possibly in a library? Somewhere in the Wirral is a copy of this sign!!

Adam's Weekly Courant of 2 January 1757 records the wreck of the ship Cunliffe,

from Virginia, laden with tobacco, etc. She took the ground on Mockbeggar Wharf;

was floated off but "a violent storm" arose and drove her ashore on the main

opposite Wallasey Church, where doubtless the inhabitants gave her their

unwelcome attention. We gather from Mr Kitchingman's notes that contraband was

temporarily hidden in Mother Redcaps and surrounding grounds. The goods were

removed later secretly over the moor, through or round the then small village of

Liscard, along a lane (now Wallasey Road) and down the old lane, now the

footpath to Bidston, right on to the Moss where the road as such ended. It was a

most difficult and dangerous passage to Bidston, the only way being round by

Green Lane, Wallasey, and past Leasowe Castle. Many people who attempted to

cross the Moss without a guide, as late as 1830 became bog foundered and had to

be rescued. The Moss, undrained till the making of the Birkenhead docks in 1844,

was full of cross pools, morasses and long, winding inlets forming a kind of

labyrinth. There was only one reliable but tortuous passage over it.

The smugglers

concealed their contraband in the cottage. When the coast was clear, they moved

it secretly, probably at night, over Liscard Moor behind the cottage and through

or round Liscard, along Wallasey Road and down Breck Road, then down the old

footpath to Bidston and out on to Bidston Moss where the road ended. This was a

hazardous route, but the only way round was via Green Lane, Wallasey, and past

Leasowe Castle. If it were reported (secret signs) at the "jaw bones" or on the Bidston side of the Moss that it was not safe to proceed to Bidston, the contraband was diverted to the westward along the edge of the Moss and taken to the old Saughall windmill. This was a most remarkable structure, built of wood with strong oak beams and gaunt, primitive sails standing on a rough base of stone, with a large wheel on the ground for turning the mill round. The mill stood entirely by itself, a little way from the edge of the Moss but a full mile away from the village of Saughall Massie. Secret meetings of various kinds, political and otherwise, were held in this old mill, which was the home of numerous ravens and said to be haunted. It was repaired and in use, and is shown in the Ordnance Map of 1840, but shortly after was demolished and later still a large house built on the site.

From Bidston a packhorse track continued in a southerly direction under the

skirt of Bidston Hill and Wood to Noctorum, then southward along a narrow,

packhorse road (too narrow for carts) and along a rough stone causeway, the

stones of which are still to be seen for half a mile between Prenton and

Storeton. Another hiding-place may have been a cave in the Yellow Noses, for the

walls were profusely decorated with incised dates and initials, the earliest one

being 1619. This cave had a narrow opening, which was obscured by a landslide

some years before the promenade works made entry impossible. The cave was

accessible from the garden of the house above, called Rock Villa. In the cavern

proper is a well, which no doubt proved valuable to those who frequented it, and

the air is quite fresh even at the furthest end, showing that there must be an

outlet. There are several interesting stories of tricks being played by the

smugglers on preventive officers but it is difficult to get authentic

particulars. One is told of information being given to a preventive officer at

Mother Redcaps that two kegs of rum were about to be taken in a donkey-cart to

Bidston via the Moss. As he lay in wait near Liscard, the donkey-cart came along

and was pounced upon by the waiting officer, but on examination the kegs were

found to contain ale which was stated to be for the Ring-if-Bells (2008 image

left) at Bidston

where a shortage had occurred. The rum had been removed from the kegs and sent

on in cans by another route to be replaced in the kegs on arrival. PRESS GANGS The Royal Navy was not the elite volunteer Force we know of recent years. Life was hard, very hard, with bullying common. Merchant ships ran the gauntlet of Naval Press Gangs, not only locally, but across the world. Merchants would be boarded almost anywhere and sailors "pressed" into service with the Navy leaving the ship with barely enough sailors to make the trip home. Even when in home waters, they were not safe, many a merchant limped into harbour with a skeleton crew. Ship owners, mindful of this, would have spare men available, carpenters, riggers and longboatmen etc, who would be taken out, into Liverpool Bay, to take over merchants to bring them in to dock.

However, more

of a danger existed when the sailor that did dock, made it to shore. When a ship

docked at Liverpool, for example, the sailors would come ashore and head for the

Taverns and brothels so long associated with docklands everywhere. After a few

drinks he would leave a particular tavern to head back to his ship. Waiting in

the dark alleys would be maybe a Royal Navy ensign or Midshipman with a couple

of burly crewmen. Marlin spike on the head, and another volunteer had joined the

Royal Navy, waking up in the bowels of a frigate or suchlike. Such was the dread of this, that sailors would take to the boats that they might conceal themselves in Cheshire. The men would "abandon ship" in Liverpool Bay, rowing ashore near the "Red Noses" on what is now Kings Parade, New Brighton, to hide in the wilds of Cheshire. When their ships were ready to sail, they would return. A visitor to Mother Redcap's at this time describes it "as a little low public house known as Mother Redcaps, from the fact that the owner wore a red hood or cap". This is not by all accounts the definitive reason for the name, it may be just the writer's observation? But this is the generally accepted reason for the name. Red noses was rumoured to house tunnels which led to Mother Redcap's, and quite possibly, other destinations inland. Naturally, any further investigation was discouraged. This was not without risk. Wallasey Parish Church (St Hilary's) Register records the death by drowning of William Evans, escaping a cutter on 29th March 1762 and of John Goss, sailor, drowned from the Prince George. The Prince George was a Naval tender used to ferry those "pressed man" into service on board waiting ships, lying in Liverpool Bay. John Goss could either have been a regular sailor or someone trying to escape. The reason for his death by drowning is not known. Mother Redcap was, by all accounts, so "far out of the way" that the only approach was by boat. But, the smugglers knew the ways across the Moor behind.  The End ........................ vandalised and derelict Return To Mother Redcaps - a poem by Christopher George And it's men to your

oilskins and women your shawls,

Description of Mother Redcaps by Gavin Chappell in his book Mother Redcaps was built of red freestone, and the walls were practically three feet thick. There were two mullioned windows at the front, and the walls were covered by thick planks of wood from wrecked ships. Eventually this timbering fell off at some point before 1857, when the first painting of it was made, and it was never replaced. There was a front door made of five inch thick oak, studded with iron nails, and seems to have had several sliding bars across the inside. Just inside the door was a trapdoor leading down to the cellar under the north room, a rough wooden lid with hinges and shackles. lf an intruder forced the front door this would withdraw the bolt of the trapdoor, precipitating the unwelcome visitor into the cellar, eight or nine feet below. lt was also used for the more mundane purpose of depositing goods. If a visitor had successfully negotiated this initial obstacle, they would have the options of entering a room to the north or another to the south (although this entrance would be covered by the open front door), or going straight up a staircase directly ahead of the door. The main entrance into the cellar was behind this staircase, where seven or eight steps led down. At the top of the cellar steps, a narrow doorway led out into the yard at the back. Behind the stairs was also a door leading into a kitchen at the back of the house, from which the yard was also accessible. The beams in the two main rooms of the house were made of oak, and the chimney breasts were very large inside. There were cavities near the ceiling, over the oak beams that had removable entrances from the top of the chimney breasts inside the flues. In the south room was a small cavity, just large enough to conceal a small man. ln the wall were other smaller cavities where Mother Redcap kept the earnings and prize money of privateer crews while they were at sea. In the yard was a well, twelve foot deep, dry and partly filled in with earth. On the west side of the wall of the well (facing inland) there was a hole that seemed to lead into the garden but probably led to a mysterious passage. Also at the back of the house was a small stream, supplying the house and also used by the boats that anchored nearby. A brew-house was also to be found in the yard, and the place was noted for its homebrewed ale as late as 1840. At the south end of the house there was another cave or cellar, and a mosaic was placed over sandstone flags that covered this cavity. A square hole with steps, made to look like a dry pit well, was the entrance to this cellar. Much of the yard seems to have been hollow, flagstones on beams covering a large subterranean space. A manure heap and a stock of coal were piled on top of it; the coal was brought in small boats called "flats" and Mother Redcap sold it to the people of Liscard. When contraband was concealed inside the cave, the coal and barrels were moved to cover the entrance. At the end of the cave was the mysterious passage mentioned above. Some sources state that it led to the Yellow Noses, over a mile away in what is now New Brighton, and also that another passage went to Birkenhead Priory (see next chapter). More conservative accounts say that it led to an opening in a ditch that led to a pit about halfway up what is now Lincoln Drive, in the direction of Liscard. On the edge of this pit grew a willow tree which was used as a lookout post from which one of Mother Redcaps confederates could survey the whole entrance to the Mersey. The shore in front of the house was made up of pebbles and star grass, and had stone sidewalls running down to the strand on either side, to counter the flood-tide. The north wall, which was very strong, was used as a shelter for boats and had thick wood posts on its top where boards could be slid to increase the walls height. Despite these precautions it was not unknown for the cellar to be flooded at high tide when there was a north-west gale.

All ye that are weary come in an take rest, |

| The following narrative was written by Gavin Chappell, a reknown Wiral historian, who has given me permission to reproduce it here, on my own page. Its possible that it may repaeat some of the information already published above, but they were fron different, unidentified, sources. However, I put it all right by thanking Gavin and showing his immense contributions to Wirral History. | |

|

Whatever happened to Mother Redcap’s Treasure? Pirate’s Gold and Smugglers’ Tunnels. We’ve all heard rumours of Wirral’s piratical past and its connection with smuggling in the eighteenth century. Many have heard of Mother Redcap and the legendary smugglers’ tunnels beneath Wallasey. Mother Redcap’s death, however, enshrines a mystery; a £50, 000 privateers’ prize had been entrusted to her care, but after she died it was never seen again. Whatever happened to Mother Redcap’s treasure? Was it spirited away into the labyrinth of tunnels riddling Wallasey’s bedrock? GAVIN CHAPPELL reports on what little is know of the lost treasure of Mother Redcap… Part One – Mother Redcap’s Treasure In the eighteenth and early nineteenth century Wallasey gained a reputation as a haunt of smugglers and pirates. The centre of local smuggling was Mother Redcap’s, a tavern that once stood on what is now Egremont Promenade. It was nicknamed Mother Redcap’s after its proprietor, an elderly lady called Poll Jones, who always wore a red cap or bonnet. Mother Redcap was a great friend to smugglers and privateers, gaining a reputation as the “foster mother of wild spirits.” The tavern was rebuilt as both a hiding place for smuggled goods, and a potential death-trap for unwary customs men. Mother Redcap herself was very likeable, and assisted sailors by acting as a banker, minding their earnings while they were at sea. Many of the clientele came from the crews of privateers who anchored at Red Bets, the anchorage just opposite the tavern. Mother Redcap’s was built of red free-stone, and the walls were practically three feet thick. Smugglers hid contraband in the walls and ceilings of lower rooms. The walls were covered by thick planks of wood from wrecked ships. There was a front door made of five inch thick oak, studded with iron nails, and seems to have had several sliding bars across the inside. Just inside the door was a trapdoor leading down to the cellar under the north room, a rough wooden lid with hinges and shackles. If an intruder forced the front door this would withdraw the bolt of the trapdoor, precipitating the unwelcome visitor into the cellar, eight or nine feet below. It was also used for the more mundane purpose of depositing goods. If a visitor had successfully negotiated this initial obstacle, they would have the options of entering a room to the north or another to the south (although this entrance would be covered by the open front door), or going straight up a staircase directly ahead of the door. The main entrance into the cellar was behind this staircase, where seven or eight steps led down. At the top of the cellar steps, a narrow doorway led out into the yard at the back. The beams in the two main rooms of the house were made of oak, and the chimney breasts were very large inside. There were cavities near the ceiling, over the oak beams that had removable entrances from the top of the chimney breasts inside the flues. In the south room was a small cavity, just large enough to conceal a small man. In the wall were other smaller cavities where Mother Redcap kept the earnings and prize money of privateer crews while they were at sea. In the yard was a well, twelve foot deep, dry and partly filled in with earth. On the west side of the wall of the well (facing inland) there was a hole that seemed to lead into the garden but probably led to a mysterious passage. At the south end of the house there was another cave or cellar, and a mosaic was placed over sandstone flags that covered this cavity. A square hole with steps, made to look like a dry pit well, was the entrance to this cellar. Much of the yard seems to have been hollow, flagstones on beams covering a large subterranean space. A manure heap and a stock of coal were piled on top of it; the coal was brought in small boats called “flats” and Mother Redcap sold it to the people of Liscard. When contraband was concealed inside the cave, the coal and barrels were moved to cover the entrance. At the end of the cave was the mysterious passage mentioned above. Some sources state that it led to the Yellow Noses, over a mile away in what is now New Brighton, and also that another passage went to Birkenhead Priory. More conservative accounts say that it led to an opening in a ditch that led to a pit about halfway up what is now Lincoln Drive, in the direction of Liscard. On the edge of this pit grew a willow tree which was used as a lookout post from which one of Mother Redcap’s confederates could survey the whole entrance to the Mersey. Mother Redcap had hiding places for any number of fugitive sailors, and of course she also acted as a banker, keeping the men’s earnings and prize-money concealed about the building, and it was said that she had enormous amounts of money concealed, but its location was never revealed. It is said that shortly before her death a privateer ship came into port in Liverpool with a fabulously rich prize that had given the crew at least £1, 000 (£50, 000 in today’s money) each. Mother Redcap’s was “swarming” with sailors from this ship, and she received a great deal of the prizemoney for safekeeping. She died soon after, and little property was found in her possession. The location of the privateers’ prize money remains a mystery to this day. After Mother Redcap’s death the tavern continued to be an important landmark, even after it had had its license revoked. A retired solicitor called Joseph Kitchingham bought it in 1888, restoring and renovating the building, adding a turret attic, a further wing and various enlargements and alterations, including a date plate inscribed with the legend 1595 – 1889. The property was sold after Kitchingham’s death when it was bought by Robert Myles who opened it as a café, named Mother Redcap’s Café. By the 1950s the house had come into the possession of the Grimshaw family, whose son Wolfgang was a childhood friend of local historian Joseph “Pepe” Ruiz. In the latter’s book “Beachcombers, Buttercreams and Smuggler’s Caves” he relates his experiences of the building in its later years. Digging in the south west corner the two boys got down no more than a foot before their spades met a large sandstone slab, which further excavations revealed to be part of a set of steps leading downwards. Mother Redcap’s was never a success as a café. It also failed as a nightclub – the aptly-named Galleon Club -- and closed in 1960, falling into ruin before being demolished in October 1974. Joseph Ruiz records that during the demolition a bulldozer fell through a hole in the ground, revealing a large well with an entrance door part of the way down. The workers recognised this as the famous “smugglers’ well” and one man suggested his mates lower him down to the door and they inform the museum authorities. The foreman, however, insisted that the well be filled in, and threatened instant dismissal to anyone contacting the museum. Mother Redcap’s secrets were finally buried. Soon after, a nursing home was built on the site, and it still stands today. Part Two – Smugglers’ Tunnels A 1974 article in the Wirral News stated that the developers found no trace of tunnels while building the nursing home on the site of Mother Redcap’s. However, Joan McCool of Rivington Road, who had worked at the Galleon Club in the fifties, said that behind the bar there had been a large bank with several tunnels that had been partially filled in with beer bottles. To the left of the bar there was a large slit, which would go unnoticed unless drawn to a visitor’s attention. This could be entered sideways, and led to a black, damp tunnel running behind the bar and seeming to go on much further. Inga Kneale, the Galleon Club’s former proprietor, said that although she had never found tunnels “of any length” she was sure that they existed, and had always felt that someone was watching her. A previous owner had excavated the dance floor while searching for the passages, but had been unsuccessful. A geo-physical survey in the mid seventies by Ezekiel Palmer of the Proudman Institute also failed to reveal any sign of tunnels. However, a letter from Marion Fisher, former owner of an hotel in Wellington Road, mentioned a long stay resident, a builder, who had been working on Mother Redcap’s. Part of his work had been to fill in the well, which this account describes as “square and situated at the front of the house.” He told Mrs Fisher that down the well were three entrances to tunnels. Some of the tunnels had caved in, but the one that ran to St Hilary’s was intact. Another ran “under some nearby cottages” while the third was “believed to run somewhere via the docks to an old Birkenhead church, possibly the priory”. The nineteenth century writer James Stonehouse recorded having “been up the tunnels or caves at the Red and White Noses many a time for great distances,” and how he “once … went up the caves for at least a mile, and could have gone further.” He believed that they were “excavated by smugglers in part, and partly natural cavities of the earth.” Elsewhere he records the tradition that “the caves at the Red Noses communicated in some way and somewhere with Mother Redcap’s.” Other accounts say that a second tunnel led from the Priory to Mother Redcap’s. In 1897, “an old man who had explored them in his youth” was living at Wallasey, The most famous of the caves, known as the Wormhole, lies beneath Rock Villa. The sea entrance was blocked off after the construction of the Promenade, but until recently it could be entered via a manhole and a vertical ladder from the garden of the house. Formerly opened each year for charity, the cave consists of a narrow tunnel on a north-south axis which opens out into a main cavern containing a well, and a bricked-up tunnel on the east wall. Several dates are carved on the walls, including one as early as 1619. The air is said to be fresh, even at the southern end, so there must be an outlet. Recent rumours, however, suggest that the owner has barred off the entrance. It is said that the tunnel is linked with others in a cavern underneath the Palace Amusement Arcade in New Brighton. Tradition maintains that smugglers and wreckers concealed their booty in the cavern, which is sadly no longer accessible. The tunnels are believed to lead to Bidston, Mother Redcap’s (from which another tunnel is supposed to lead to Birkenhead Priory), St Hilary’s Church and Fort Perch Rock. The existence of the Fort Perch Rock tunnel itself was confirmed by a geo-physical survey carried out in the mid-seventies, (at the same time as the one at Mother Redcap’s) and it has been suggested that it was built as an escape route for the fort in case of attack. The cellars of the Palace itself consist of an extensive warren of tunnels that predate the current building by a substantial if uncertain period, being lined with handmade brick joined with cement rather than mortar. The Old Palace and the Floral Pavilion were built in 1880, opening on Whit Monday the next year. It included an aquarium, baths, a theatre, a ballroom said to have been the finest in England, an aviary, and a zoo. During the construction of the original building a pit was discovered which “revealed evidence that it had been used by smugglers and wreckers for the purpose of concealing their goods” and that possibly it hid something more sinister. A “sickening” stench emanated from the pit, and only the liberal use of disinfectants could eventually remove the contents so work could continue. According to local traditions, this is connected with the wreck of the Pelican in 1793. The cavern was transformed into an underground waterway known as The Grotto, where small boats could sail past illuminated caves. It extended for over 250 metres, and is said to have ended beneath the bottom of Rowson Street. The passages are said to extend as far as St Hilary’s, Leasowe Castle, and even Chester Castle. Although the latter seems highly, it is possible that the tunnel leading to St Hilary’s joins up with one of the tunnels from beneath the Palace. Perhaps they are one and the same tunnel. No tunnels are currently accessible from St Hilary’s at the present date, and the vault beneath the old tower was covered by a tiled floor in the late nineteenth century. But according to the rector, Canon Paul Robinson, one of the parishioners remembers going down a tunnel in the thirties, below Swinton Old Hall, the site of the modern rectory, a few hundred years away from the old tower. Joseph Ruiz says that a well exists beneath the front sitting room of the old rectory, fifteen feet wide and 350 feet deep, and it is believed to lead to a tunnel; this is also mentioned in an article in the Wirral News. The article refers to a legend that says an underground passage leads from the rectory to the church (presumably the old tower) and then on to Mother Redcap’s. According to legend, Mother Redcap’s treasure – the missing prize money of the privateers - lies somewhere in this tangled labyrinth. But what happened to it? Is it lost forever? It is possible that some of the treasure has been found over the years. Mother Redcap’s death appears to have been during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. In about 1850, a “quantity of Spade Ace guineas was found in a cavity by the shore,” which is the origin of the name Guinea Gap. The money dated from the late seventeenth to mid eighteenth century (William and Mary, George I and George II), and was found with a sword and a skeleton. According to Joseph Ruiz, a man named Morty Brightmore was employed by the Pioneer Corps in 1942. One of his duties was to dig sand out of the Red Noses caves for use in sandbags. While so engaged, he found an old leather purse filled with gold coins, which he reported to the officer in charge of the operation. It is said that the officer gave the coins to a jeweller to be melted down to make a bracelet for his daughter. In 1979, Bob Wadsworth, owner of the end house in Seymour Street, was clearing out his cellar when he found the entrance to a large tunnel beneath some bricks. The tunnel led in the direction of the sea. Investigating the tunnel, Bob found an old, rotten bag of silver coins, which he sold to local antique dealer Frank Upton for £3 and two packets of cigarettes. As is so often the case, the council later filled in the tunnel. The current writer frequently found himself up against a brick wall – sometimes literally – as he struggled to uncover the truth behind these rumours. Tunnels had been blocked up as soon as they were discovered; the publication of Joseph Ruiz’s book apparently resulted in the blocking of all the Red Noses tunnel entrances; documents had mysteriously vanished from the reference sections of libraries whose staff were oddly brusque and unhelpful: finally, the writer was warned that all information on the subject had been suppressed by the local authority. It remains an enigma. |

|

| Fortunatus Wright | |

More of a 'pig sticker' than a sword, this was his sword. Image: Gavin Roach |

In 1732 he married Martha Painter of his home village Wallasey in Wirral, and they had a number of children, including a daughter, Philippa. Martha died shortly after, and in 1736 Wright married Mary Bulkeley, daughter of the Anglesey squire and diarist William Bulkeley. Mary had been staying with relatives in Dublin since 1735. A disappointment to her father, his disappointment greatly increased when his daughter wrote to him requesting speedy consent of her being marryed to [Fortunatus] Wright forthwith whereby she may prevent all further trouble..She was carrying his illegitimate child. Wright wed Mary in Dublin, and then visited Bulkeley, He notes in his diary that Wright shows a fondness to his wife always playing with her, and kissing of her. Shortly afterwards, Fortunatus Wright took his new wife back to Wallasey to meet his family. Sadly, Mary miscarried shortly after. Although Mary gave birth to a daughter, Ann, the next year, the marriage rapidly became unhappy, and Bulkeley refers in his diary in 1741 to the barbarous usage and insults received by my Daughter from her husband who thereupon went a rambling towards Dublin. On returning next February, Fortunatus Wright set out with his wife for Wallasey, but it seems they quarreled again, and he abandoned her in Beaumaris. Like any Byronic hero-villain, he headed for the Continent. In Italy, he was challenged at the gates of Lucca, but refused to hand over two pistols to the guards. He aimed one at the soldiers, threatening to kill them. A colonel took Wright prisoner and kept him under guard in his inn. Three days later, he was escorted from the city-state and forbidden to return. |

|

He settled down as a merchant in Leghorn for four years, during which time he knew John Evelyn, great-grandson of the famous diarist. Meanwhile, the War of the Austrian Succession, which Britain and France soon entered on opposing sides, had begun. In January 1744 Fortunatus Wright became personally involved when a French privateer took his ship, the Swallow, and ransomed her at sea. This stirred Wright to fulfil his patriotic duty or perhaps his motive was simply revenge. He fitted out the brigantine Fame to cruise against the enemies of Great Britain. In December 1746 The Gentlemens Magazine reported that Wright had captured sixteen French ships in the Levant, worth £400,000. On 19 December Fame seized a French ship with baggage aboard belonging to the Prince of Campo Florida. The Prince was angry, as was Goldsworthy, English Consul at Leghorn, who urged Wright to set the prize free. Wright refused, but agreed to refer the matter to the naval commander-in-chief, who decided against him. The prize was released. In 1747 the Sultan complained that Wright had seized Turkish property aboard French ships. Goldsworthy demanded an explanation. Wright replied that the ships in question had French passes and hoisted French colours while fighting him. The British Government ruled that Turkish property aboard French vessels was not prize. Wright refused to allow this order to be retrospective, and declined to give up the money. Orders came from England to arrest him and send him home. The Turks imprisoned Wright in Leghorn Fortress but for six months refused to hand him over to Goldsworthy. In June, Goldsworthy was ordered to free Wright because the privateer was prepared to stand trial. But by this time the war was as good as over. In August, Mary set sail from Liverpool to join her husband at Leghorn, but it does not seem that she received a happy welcome. Wright had settled down in Leghorn as a merchant, although the law case dragged on, and he profited less from peace than he had from war. He vented his frustration on his wife, and her father received a letter in 1751 complaining of his cruel conduct. Back in England, in 1755, Philippa, Wrights daughter by his first marriage, married Charles Evelyn, son of John. Meanwhile, however, the clouds of war were gathering across Europe once again The Seven Years War, in many ways a continuation of the War of the Austrian Succession, broke out in 1756. Wright built a vessel, the St George, to bring the war to the French. A French privateer had been cruising off the harbour for a month: Louis XV had promised a generous reward to whoever took Wright, dead or alive. Wright applied for a permit for four small guns and twenty-five men. Obtaining it, he sailed out of Leghorn with four merchant vessels. Outside Tuscan waters, he bought more guns from the merchants and got fifty-five of their men to come aboard his ship. Next morning, the French privateer bore down on them. In the battle, Wright lost his lieutenant and four men, but a lucky shot carried away the prow of the French privateer on which thirty men were trying to board the St George. Two other enemy privateers appeared and stopped Wright from pursuing their colleague. Wright brought the merchants back to safety. The English merchants in Leghorn rewarded Wright, but the Tuscans detained him for breaking the agreement. The Governor ordered him to come within the harbour or be brought in under force. Wright refused. Two ships anchored alongside the St George and took charge. The English captains were angry, but Wright chose to place himself in the hands of Sir Horace Mann, British Resident at Florence (capital of Tuscany). Leghorns governor charged Wright with deceiving the authorities and disobeying orders to come within the harbour. Mann pointed out that the battle took place twelve miles off; besides, the Frenchman was the aggressor. As to their orders, they had no business to give them. Admiral Hawke, naval Commander-in-Chief, sent Sir William Burnaby to demand Wright be given up. Wright was released and carried off in triumph. Next, he put into the port of Malta. The Maltese proved as partial to the French as the Tuscans, and Wright was not allowed to buy slops and bedding for his men. He was ordered to send ashore the English mariners he had received on board the St George. Wright refused. A galley came alongside, the captain being under orders to sink Wright if he lifted anchor, and to board and kill everyone if he resisted. They dragged the mariners Wright was protecting from the privateer. The St George left Malta without stores. A day later it was pursued by a large French privateer that had been in the harbour. Wright played with the larger ship, sailing round her, the St George was twice her speed. In the next two months Wright harried French shipping, winning many prizes. Louis XV fitted out two ships, while the Marseilles Chamber of Commerce prepared another ship, to seek and destroy Wright. The Hirondelle of Toulon also set out after him and they fought in the Channel of Malta. Wright defeated the French ship and both put into Malta to refit. His own vessel had taken several shots under the waterline, but the Maltese refused to allow Wright to heave down. Mann had been working hard to convince the Tuscans that their restrictions on British shipping were ruining trade. He obtained permission for Wright to send his prizes to Leghorn, and wrote to him to inform him that he could return safely. It is not known if Wright ever received this letter. |

|

|

Mary was cheated of Wrights fortune by Philippa Wrights husband, Charles Evelyn. Destitute, her children made their way back to their grandfathers house in Wales, followed by Mary. After this, William Bulkeley wrote of nothing in his diary except the weather until his death. In his History of England, Tobias Smollett called Fortunatus Wright this brave Corsair, while Gomer Williams referred to him as the ideal and ever-victorious captain around whose name and fate clings the halo of mystery and romance. In his day he was famed as the privateer who defied the French and won rich prizes. His philandering and his troubled second marriage were revealed when Bulkeleys diary was discovered in the early twentieth century. Wright is even remembered in Finnegans Wake. But in Wallasey, the town of his birth, Fortunatus Wright is entirely forgotten. Sept 2009: Note: Fortunatus Wright is now featured in Gavin Chappell's new book Wirral, Smugglers, Wreckers & Pirates. A Countyvise publication. ISBN 978-1-906823-20-7 anda ebook on oldwirral.com |

|

|

Reference but not sources http://www.nelsonsnavy.co.uk/broadside7.html http://www.old-merseytimes.co.uk/pressgangs.html A book on Smuggling on the Wirral - click here Footnote: Source: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fortunatus_Wright by Gavin Chappell |

|