Moreton Page 5

Shanty Town

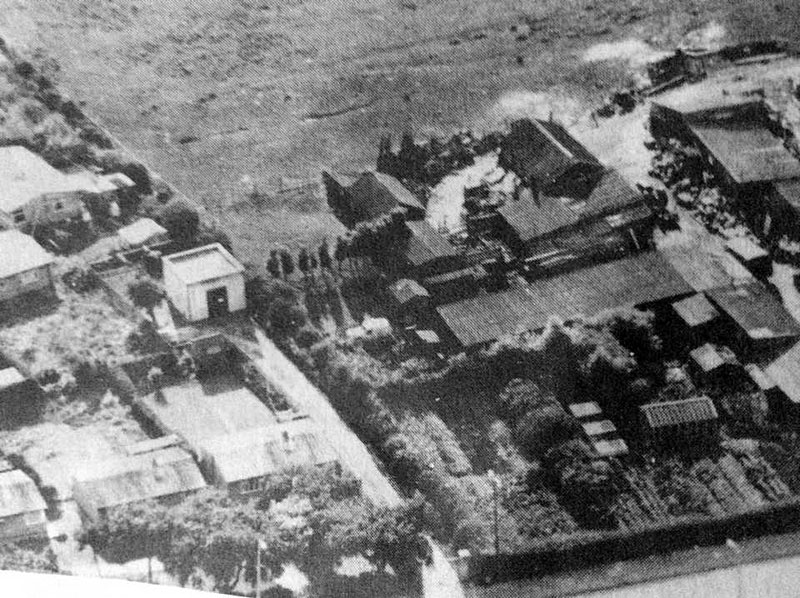

Life in the shanty town on Moreton Common earlier this century. I would like to point out that I have absolutely no idea who wrote this. It appears in the Wirral Journal Autumn 1991.

Local folk will have been aware of the invasion, during July, of hordes of itinerant travellers looking for a place to settle for a while on Wirral. The problems experienced on Moreton Common during this past summer, whilst worrying, are nothing really new to this part of the peninsula. These wide, open spaces by the sea have lured folk of a somewhat similar disposition in times past; hear what a rambler said of his visit to Moreton about the early 1920s: ‘Till pretty recently, Moreton was no more than a tranquil cluster of old Wirral homesteads, but just at present its name is associated with contention by reason of a number of camp dwellers, whose wholesome aspiration for liberty and love of nature is not uncharacteristic of the soil. You catch something of the new atmosphere on stepping down towards the village. Almost the first house you come to is called “Jocular Cottage” and the next is dubbed “Rainfall Villa”. There is such a merry and-bright don’t care if it snows air about the choice of titles that you anticipate more novelties, but you do not find them.’

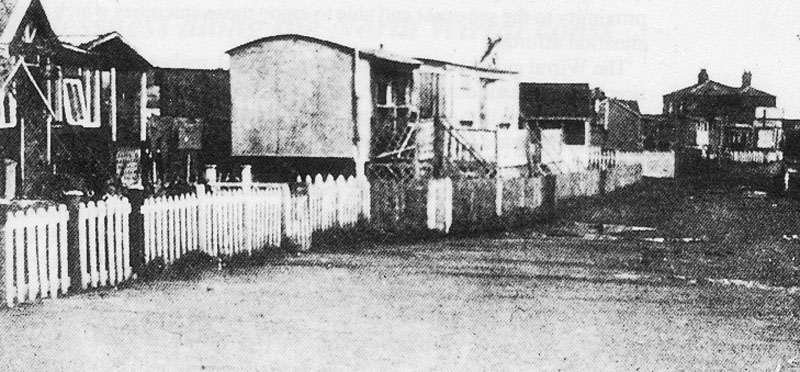

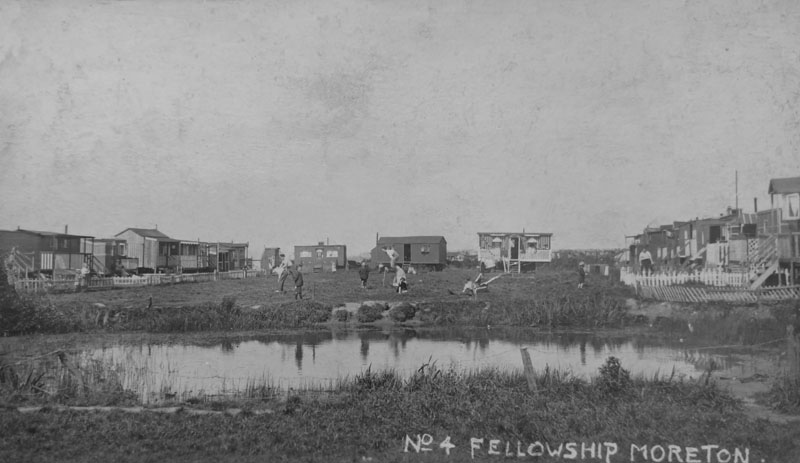

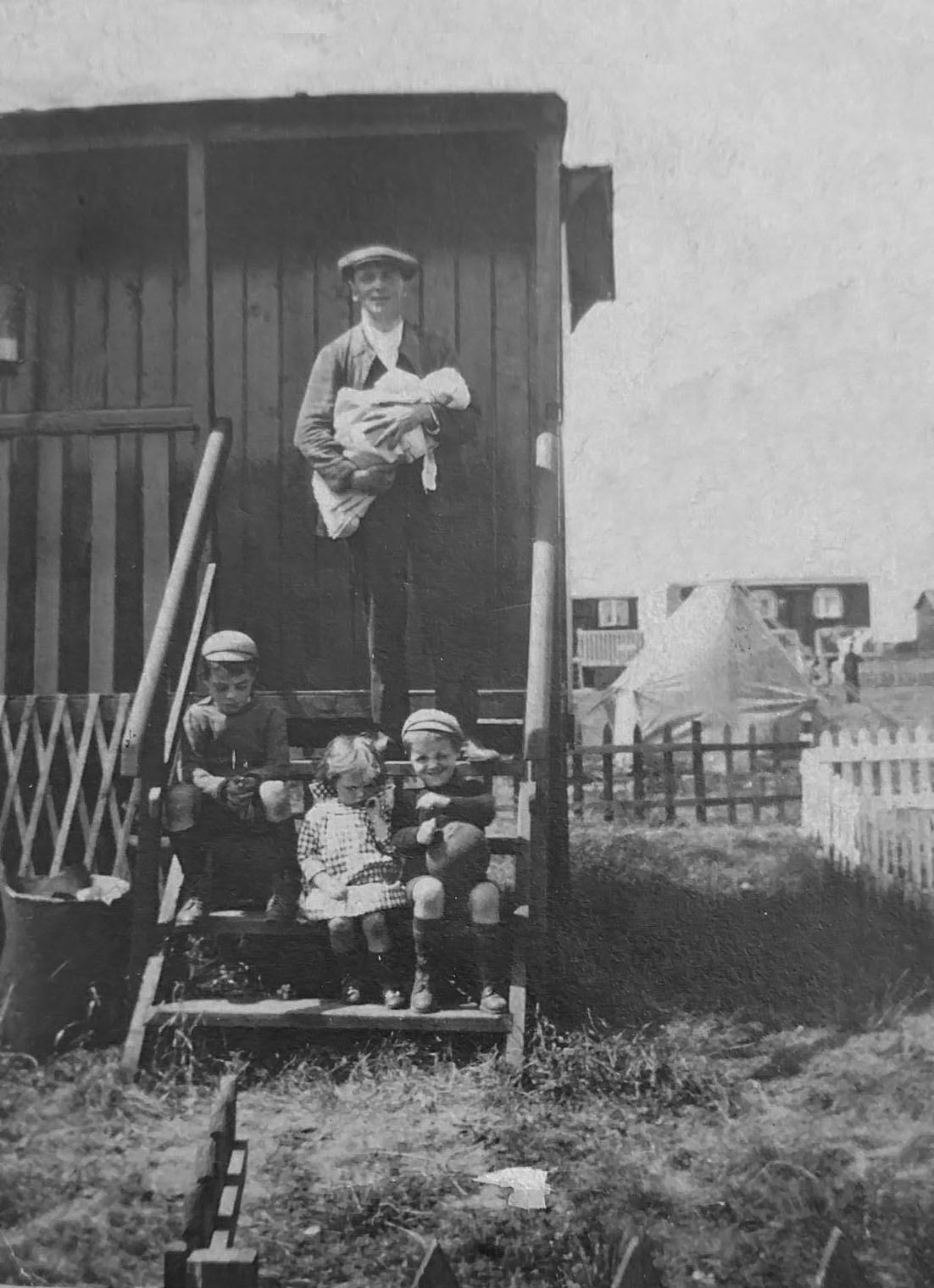

Like today’s ‘travellers’, these folk had no permanent homes of their own, and many were suffering the effects of the post-war depression. So they flocked to this damp, low-lying part of Moreton, particularly on Kerr’s and Fellowship Fields, and erected make-shift chalets and huts, caravans, bungalows, and even old railway trucks. Facilities and services were non-existent: water was obtained from standpipes, and sanitation was primitive, to say the least!

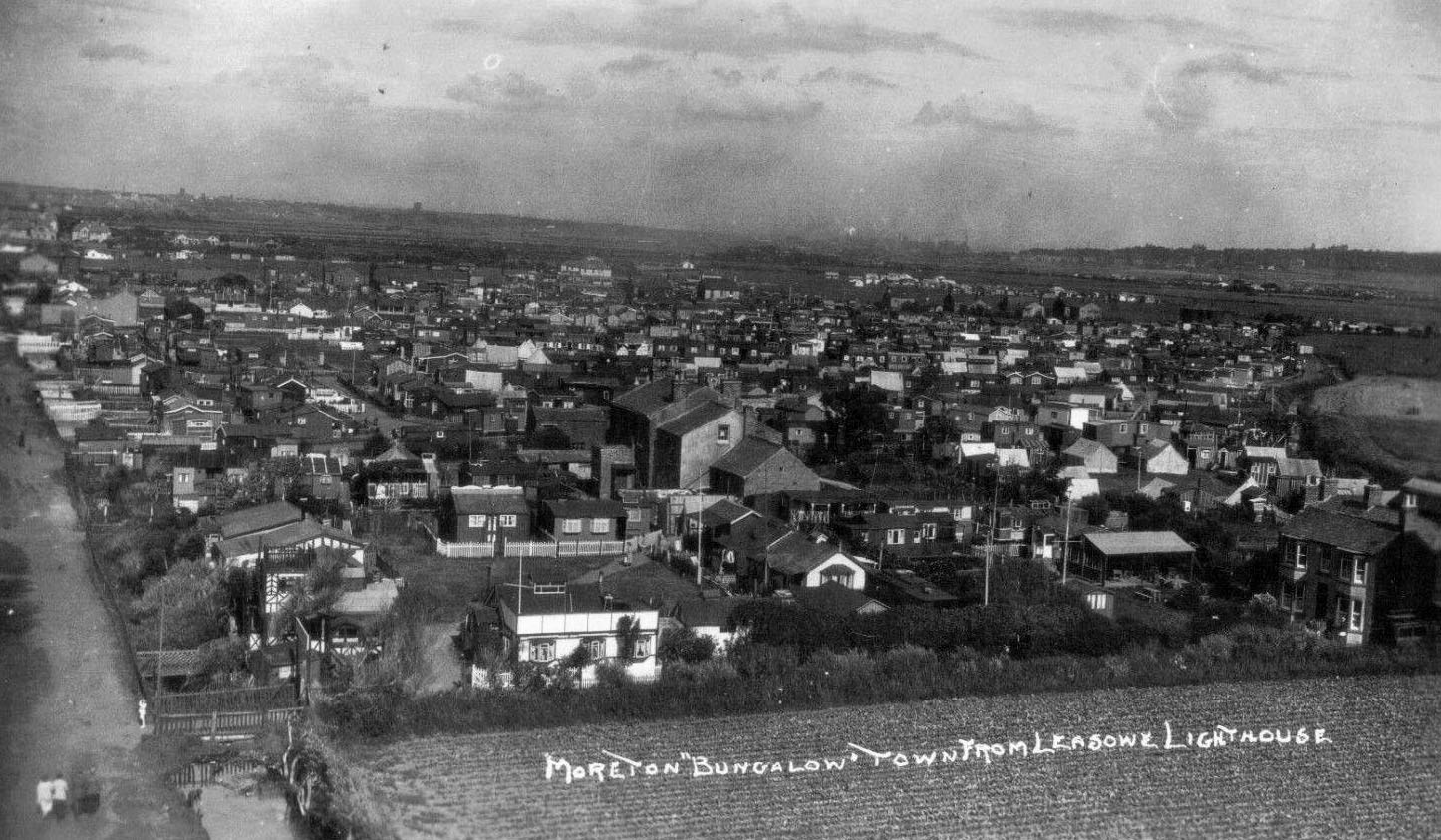

A guidebook of the time described the scene: ‘The most distinctive feature of Moreton is to be found on the flat land near the shore, where one storied wooden dwellings have been put up in such numbers as to form a veritable Bungalow Town; caravans and marquees are also used as habitations. Many of the bungalows are unexceptional both as to design and convenience; but there are others whose suitability for occupation is by no means obvious; and the wooden structures erected to serve as shops do not add to the picturesqueness of the scene. Their presence has led to certain difficulties with the local authorities and there is also distinct liability to flooding after heavy rain.’

That was something of an understatement: almost every photograph taken of Moreton’s ‘shanty town’ shows folk with their trousers rolled up. The womenfolk were often taken to Moreton Cross in a punt to get their shopping; and they always carried a towel in their baskets to dry their feet after paddling through the mud and water. The authorities look upon the scene with some displeasure; the 1929 Borough Plan states: ‘In this district of Moreton there exists, unfortunately, a large number of caravans, shacks and bungalows, the existence of which has placed upon the area a stigma, the eradication of which will take some considerable time. Not only are these erections unsightly, but the living conditions are exceedingly bad; their removal is a task which should be undertaken without delay.’

The Report went on to insist on the necessity for offering alternative living accommodation; this should be in the same area, for these folk had ‘in all probability settled there for the reason that they would be in close proximity to the sea coast and able to enjoy those amenities which such a situation affords’.

The Wirral guide-book previously mentioned, makes a similar suggestion: ‘The pure air direct off the Irish Sea, the bathing, and the somewhat unconventional life prove attractive to thousands; and every year witnesses an increase in the number of those who sojourn here for part of the summer.’

So, eventually the cinder tracks and the chalets, the makeshift shops and the mud, were swept away, and eventually the housing developments of Leasowe and Moreton grew up to give those ‘lovers of the soil’ four square brick walls, front pathways and hot & cold running water. And what they gained in comfort, they no doubt lost in fellowship, comradeship, and good old-fashioned fun. Moreton-in-the-mud had died Moreton-in-Wirral was born.

Taken from Moreton Station

My Great Grandfather developed a lot of Moreton in the early 1900s and he built all the little houses in the style of architecture he remembered from the Island of his birth BERMUDA, hence the name Bermuda Road. My Great Grand Father was bought to Liverpool from Bermuda by his Grandmother who was of Native America and African heritage, she was born a slave on the island and at the age of 50 she married a Liverpool sailor and left Bermuda taking her grandson with her. His name was Charles Burden he also named 'Burden Road' - 'Eleanor Road after his wife and Macdonald Road after his favourite cricketer I think plus numerous others.

He lived in a house called 'Fellowship House' on Pasture Road which is were I was born in 1947 (behind what later became Fellowship garage). His ambition was to develop Moreton into a holiday town for the people living in the inner city of Liverpool. He set up a large camp site called 'Fellowship Fields' around the house and on the fields where the Cadburys factory was later built. The accommodation on Fellowship Fields was made up of old stream train carriages raised on stilts with verandas running round them. (there are fantastic photos of them in the Frank Biddle book on Moreton).

He marketed the site/town as a cheap holiday destination to the Irish families that he had seen living in squalid conditions in Liverpool. He was a maverick but he is single-handedly responsible for the massive rise in population that happens in Moreton over this period. The Irish families loved the sea air and outdoor life and due to housing conditions in Liverpool ended up staying on the site permanently, over 2000 Irish were living on the site when it was eventually condemned and cleared.

The story goes that although sanitation was poor and conditions were rough nobody wanted to leave because it had real communal spirit with camp fires, fiddles, drinking and Irish dancing, it was by all accounts an amazing/wild place. A lot of those resident in Moreton in the 40's 50s will have originally come from this Irish community.

Moreton Memories from Frank Brownlow

Having been sent as a very small boy to live with an aunt and uncle who lived in Moreton, I lived there continuously from 1937 until 1956 at the top end of Sandbrook Lane, towards “the race course” as we called it, beyond Bertie Parkinson’s field. The village had begun to grow after WWI, a process my uncle, a builder, contributed to, but the growth that overwhelmed it came with the council housing estates after WWII.

When it came time for school, there were three choices in Moreton: the C of E school, a private school in Dawpool Drive (I think), and Barnston Lane. Since opinion at home was that the teaching was best at BL, to BL I went. My last teacher there was the formidable but extremely good and even lovable Miss Banks. She prepared us for the "scholarship" exam., which I passed with a place at Wallasey Grammar School, which had just recently become a free school. For the next 7 years I took the yellow bus to school from the Plough Inn bus-stop, but I liked to come home on the Crosville bus because it was faster.

Moreton was a tremendously healthy place--hence the TB hospital at Leasowe--but the constant wind got some people down.

Here follow some notes and recollections starting with memoranda of a visit back to Moreton in about 1972, including a conversation with old Ted Smith who lived in Sandbrook Lane, and was the sexton at the parish church when I was little.

Friday, July 9th 1972. At F.O.Paul’s former estate on Overchurch Hill. Nothing of the house but the foundations left, brambles, weeds, trees. The ground he gave to the scouts for their huge camping field is untended. The swimming pool ruined, in fact dereliction everywhere—rubbish, rubble, junk.

Looking for the old Overchurch Hill cemetery or churchyard where the famous runic stone was found, I felt thoroughly disoriented for the first time. The area of it was there, but no sign of any stones. Odd that such an ancient site should have seemingly disappeared without trace. Then I headed for the thickest brambles, and found it.

Saturday, July 11th. Beautiful day, clear, sunny, and very bright. Began with Overchurch hill again. A fifteen-year-old boy came up while I was trying to make a composite picture of the old churchyard mound. His accent was so thick that I had trouble understanding him, but he told me that a master at the Overchurch school arranged an “expedition” to dig in the churchyard. (This explained the signs of digging I saw.) He tried to show me the chief place, but it was quite overgrown with bramble. They found some skulls and bones, and he (the lad) found a silver tray and spoon, which they presumed had belonged to the church. From his jokes about “bones for the dog” I gathered that the tone of the “expedition” was curious but jocular. The boy thought the churchyard was about 200 years old, but of course the site is much older than that.

There are some scouts on the scout-field today, so some use is still made of it, though its condition is a disgrace. Photographed the old 4th Moreton Peewit Patrol’s oak, pruned a bit over-zealously, but still a great-rooted blossomer. More scouts’ tents.

Down to Moreton proper, where I learned that the parish was established in 1863, the church built by William Inman, “inaugurator of steamship emigration,” &c., ob. 1881. That the Webster family owned “Overchurch Hill” before F.O. Paul, and later owned “Leasowe Bank.” Then round the village, what’s left of it.

Mr. Smith told me that old Mr. Minnie lived in Woodchurch, opposite the church there. With the spoiling of the village they put him into a council house, which broke his heart. Old Gervase de Brotherton of Bortherton’s farm, next to Upton Manor House, is still around it seems, in a council house now. He made some attempt to hold on to his farm. He was a ferocious old chap when I was little.

My aunt tells me that a man called Vaughan built Glebelands Road. This was formerly Glebe Fields, & it belonged to the church (Ted Smith). Hoylake Road was very narrow as late as the 30s—the Dig Lane cottages had gardens, hedges on both sides. The cross was grass, a tree with seats round it. Bethell’s row of shops was houses. There was a farm where the District Bank stands. What is now Mortimer’s was a farm, too.

Monday, July 12th. Evening, fine and clear. Set out for the shore, but left it too late. Called on Ted Smith to borrow his book, had a long chat with him. He told me the names of farmers. Two before Jack Smith at the corner of Sandbrook Lane, called Jeffreys. What is now Dodd’s was Jones. Mortimer’s was Piggot. There were four Parkinses. Old Parkinson had four sons. Ted’s father worked for Mr. Parkinson.

In his day, leaving Moreton, going towards Bidston, on the right there was nothing after Stanley’s and Miss Dodd’s until Lamb’s, where the house still stands. On the other side, nothing after Orchard Road (Hawthorne Road then) until Armchair Farm and Armchair Cottage except the cottage facing the end of Chapel Hill Road, still there when I was a boy. Barnston Lane used to be Chapel Hill (Is this where the chapel of ease was?) Now follows a summary/transcript of Ted’s conversation.

“Mr. Thomas Webster of Leasowe Bank had two sons. Here every year the children had a treat, and in the evening the grownups came for dancing on the green. Mr. Colin always danced with ‘Mary Ann’, who had the cottage at the corner of Mary Ann’s Lane. She was a little round dumpy body. Ted told me stories of Little Harry Jones, who’d do anything for money. Ted was at school with him, but you didn’t have to teach him anything, said Ted, he had it all up here (pointing to his head). There was an old Mr. Jones lived on Rosslyn Drive, a relation of Jones’s, but he’d never seen Little Harry, and he wanted to. Do you know Little Harry, Ted? he asks me. Yes, I says. Well, it wasn’t long after, I heard Harry was back and I went to see him. Hello Harry, I says. Hello, Ted, How are you? I’m fine, I says. Listen Harry, there’s a gentleman on Rosslyn Drive, Mr. Jones, he’s a relation of yours, your Dad’s cousin, and he wants to see you. Will you go? Has he any money? asks Harry. He’s not short, I says. Well I’ll come, says Harry. I’ll be there at the gate, waiting for you, I says. So Harry was there, and I took him in to Mr. Jones.

"Harry took a look at him. He’s one of ’em, he says. When we got settled down, Mr. Jones looked at Harry. He’s one of ’em, he says.“If Little Harry had known how much he had, he would have stuck to him. He’d do anything for money, Little Harry, he was that sharp. “My father worked for Mr. Parkinson, and the threshing machine was there. They got down till the straw was about so high, and it was moving up and down. Ted, says Mr. Parkinson, that’s full of rats. So they got galvanized sheets and put ’em round the straw, and they brought every dog they could find. There were that many rats…well, I couldn’t tell you how many they caught. When it was all over, they made a pile of rats in the corner. That’ll do for now, says Mr. Parkinson. Next morning when Mr. Parkinson saw my father, he says, Ted, he says, did you move them rats? No, I didn’t, says my father. Well, they’ve gone, says Mr. Parkinson. And they had, every one, and it was a big pile.“It turned out it was Little Harry that took them. You see in those days, you got a halfpenny a tale for every rat you caught from the Agricultural Board, so Little Harry’d taken a sack and put them in it, and carried them away, first thing.

“Neither farmer paid him. First one says, I’m not on the committee any more. You need so-and-so—can’t remember his name, Holt Avenue, farmed between Upton Road and Saughall Massie Road. A long walk. Harry carried them to Bank’s Hill—you’re out of my district, he said.”So he never got paid?” I asked. “Oh, no, but he’d do anything for money, Little Harry.”

“There was a postman, name Pownall, came from Upton. Could do anything on a bicycle. When he delivered the letters to Dodd’s at the farm by the lighthouse, it had a big kitchen, they’d all be sat at breakfast. In through the door he’d go, never get off his bike, ride it right round the table and out again.

“The treats were formerly at Inman’s—Inman had a tower built on the house from where he could see his ships coming into the river—Mr. Inman used to come out on the lawn throwing coppers to the children.

“Squire Vyner came twice a year on rent day to the Plough, then the Druid’s Arms. On his wife’s birthday, he planted walnut trees in all the gardens.”

(The Vyners acquired Moreton along with Bidston from the Derbys at the end of the 17th century. I think my uncle Harold bought the land he built on from Vyner. No sign of them by the time I came on the scene. Their main house is in Yorkshire, near Ripon. They were jewelers in Charles II’s time.)

Ted speaks very affectionately—and admiringly—of Mr. Inman, of the Websters, of Mr. Paul. After Inman died, Leyland of the Leyland shipping line took the Manor house at Upton, then Stern (who was still there when I was a child: how vividly I remember summer mornings in June, and the cuckoo calling across the fields from Upton Manor woods). Ted told me there was a Moreton Hall where Orchard Road now is. It had a big pond to it, big enough for a boat.

Some more notes from Mr. Smith’s Recollections. Smiths—Lingham cottage (which I remember well)—Birkenhead Corporation’s care of the Common—all the tents. Old Mr. Smith was caretaker. There were sports on the Common on Bank Holiday, greasy pig and greasy pole. Crowds came. A committee arranged the sports, Roger Halsey being one. Leasowe Bank, the Websters’ house. Mr. Smith’s grandfather who lived on Reeds Lane was the gardener there, his uncle a handyman. Barton house stood where Lloyd’s Bank now is. Holt Avenue farm belonged to Evans. Church Farm was where the District Bank is. Carr Farm now held by Mr. Smith’s cousin. Millhouse farm. Lamb’s Farm at the Reeds Lane roundabout (I remember that). Mr. Thomas Webster was “a nice old feller.” In Mr. Smith’s day, the Wilsons lived in Felicity Cottage.

Of course, right into the mid-fifties, there was still an impressive, long, one-storey thatched cottage next to Poston’s Garage, with a large, beautiful garden of flowers and vegetables, and another opposite Chapel Hill Road. Next to Poston’s was a blacksmith’s who made my uncle a beautiful wrought-iron gate for his drive. (Its predecessor was an ordinary double-wooden one, which he loved to lean over, watching the sun set towards the parish church. Came its replacement, and his younger daughter said, “Dad no longer leans over his gate. He looks through it.”)

Opposite Poston’s, on the other of the road at the corner of Sandbrook Lane, there was Smith’s Farm (Brookland House), farmed by Jack Smith. A nice man. I loved to watch him milking his cows as I walked home from school, and I loved it, too, when the threshing machine came, driven by a magnificent steam tractor. One year a notoriously misbehaved local boy set Jack’s haystack on fire, a nasty loss for him. He was very upset, I remember.

The house was a fine, typical Wirral house of yellow sandstone, with an impressive sandstone wall. It was knocked down to make room for the Catholic Church. Bertie Parkinson pastured his cows on the field at the top of Sandbrook Lane, just past our house. He and his cows would walk past twice a day, coming and going. His farm was at the corner of Barnston Lane and Maryland—or Mary Anne’s—Lane. A grumpy old fellow. Opposite Smith’s farm at the bottom of Sandbrook lane was Stanley’s Farm, run by the two Miss Stanleys. The Povalls lived in Old Hall Farm—Miss Povall taught at Barnston Lane School, I think. The Biddles were at the farm down by the Lighthouse.

During the war, Harold (my uncle) and his friend Wilf Bates had the Lighthouse and its attached land for a vegetable garden. They went fishing, too, and caught a lot of codling, whiting, fluke, and flounder, a godsend to my aunt—and a lot of our neighbours, too—in those days of tiny food rations. I took the fish round to them in parcels at two shillings or two and sixpence, and if I was lucky they’d give me a sixpence or a threepenny-bit as a tip.

Incidentally, when I was a child there were no mud flats at Moreton, nothing but miles of glorious golden sand. I remember vividly the sheer joy of being a little boy running through the water out on the sand between tides. Pollution came after the war with all the house building, and the emptying of raw sewage into the sea. In those days, too, the embankment was mostly sandstone, great blocks of it, as well as concrete.

Hard to believe, but 70-plus years ago, the north Wirral still had wide stretches of open country. It was a lovely place to grow up in. I remember riding my bicycle down the lanes, hearing skylarks overhead.

It’s been a long time since I went back, though I can feel guilty about not attending to my aunt’s & uncle’s grave in the parish churchyard. But the place is all so changed.